An ordinary man but an extraordinary talent

“He’s too miserable, he should lighten up, he’s no fun,” they say, these people who don’t appreciate the finest British sportsman of our times. My first reaction is that Andy Murray is a tennis player, not a breakfast DJ.

Moaning about his lack of jollity is like complaining, “I never listen to Chris Evans on the radio, because although his programme’s a laugh his backhand’s a disgrace.”

It infuriated me that the whole of Britain didn’t adore Murray, and I was determined to make up for this lack of reverence on my own. So I’ve followed every shot of every Grand Slam match he’s played since 2008, except for the Wimbledon semi-final against Andy Roddick, when I was in San Francisco and called the headquarters of NBC to scream that their decision to not show the match was the most despicable act their country had ever carried out, with anything they did in Vietnam a distant second.

A friend was staying at my house during the Australian Open once, and at four in the morning he came into the living room with a cricket bat, as he’d heard the nocturnal yelling downstairs and assumed it must have been a burglar. It would be an unusual burglar that kept screaming: “DON’T put your slice in the sodding net,” and “YES MURRAY WHAT A GLORIOUS ACE,” but I could understand his concern.

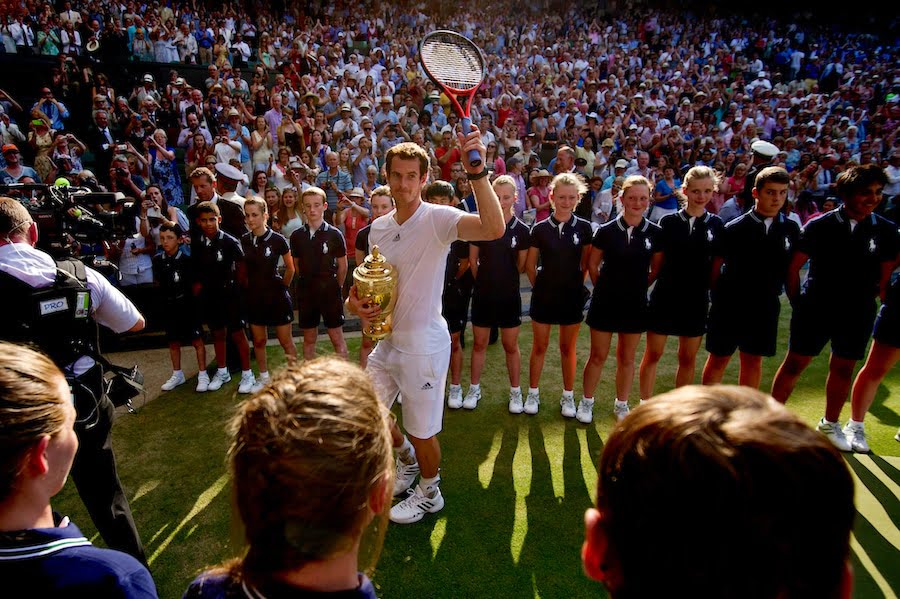

My dedication almost reached a peak on the stupendous night when he won his first Grand Slam. At the house of an equally obsessed friend, around two in the morning at two sets all, we paced manically round in circles. Taking deep breaths, my friend asked earnestly: “Mark, if it meant that Murray would break the Djokovic serve in the next game – would you have it off with Eric Pickles?” I came out of this exchange as the embodiment of calm good sense, because I replied, “No, I’d want the whole match for that.”

As with any irrational attitude, there must be a rational explanation for it, and this is the best I can do. Murray is not the classical sporting hero. Muhammad Ali, Usain Bolt and Cristiano Ronaldo are blessed with an arrogance that enhances their persona. They ooze the sense that they know they’re fantastic, and that makes them even more admirable. On the other hand, the chances of Murray celebrating a successful drop volley by dancing round the net like Raheem Sterling before posing like Kanye West are fairly slim.

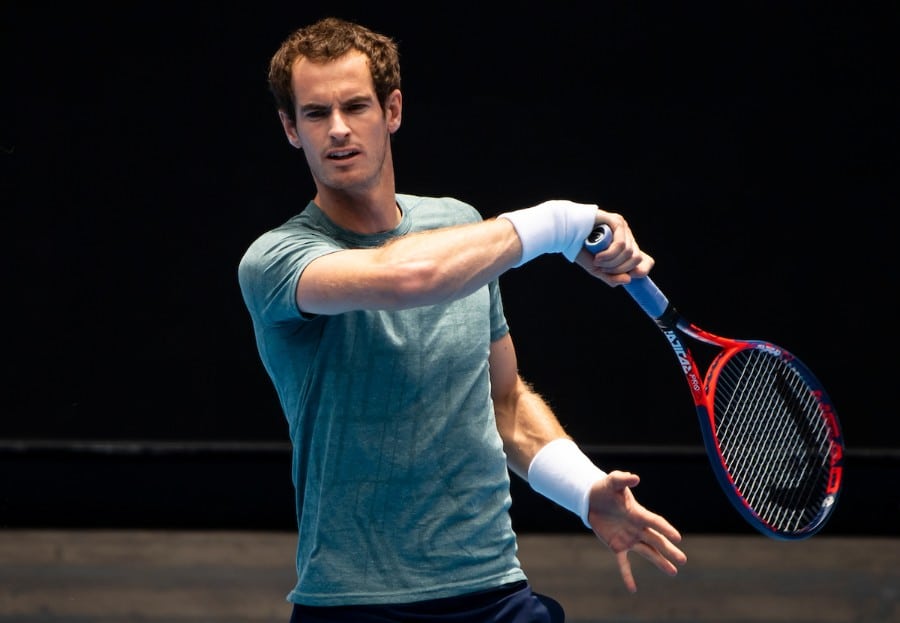

Much as I admire Thierry Henry or Serena Williams, the joy of Murray is that in every way apart from his ability to play tennis, he’s exhilaratingly ordinary. When he descends into a tantrum because he’s missed a passing shot, whacking his ankle, muttering and clutching his calf as if he’s about to say “It’s YOUR fault you useless calf, and after all I’ve done for you”, he’s behaving as any of us would.

Andy Murray seems to be himself, the ordinary lad who’s surprised when anyone recognises him, who doesn’t play the game of celebrity because he’s barely aware of it. The flamboyant sports star at full pelt is one of the greatest thrills we can witness, making us wonder how anyone can perform such feats. But when Murray defies the laws of physics to lob an opponent perfectly on to the baseline, or scamper to the net and produce an angle no mathematician has previously discovered, he achieves something even more remarkable, which is to confirm that even the delightfully ordinary amongst us are capable of feats that are quite extraordinary.

This is an extract from “An ordinary man but an extraordinary talent” by Mark Steel.

Look ahead to 2019 with our guide to every tournament on the ATP Tour, the WTA Tour and the ITF Tour

If you can’t visit the tournaments you love then do the next best thing and read our guide on how to watch all the ATP Tour matches on television in 2019

To read more amazing articles like this you can explore Tennishead magazine here or you can subscribe for free to our email newsletter here