A new tennis order is finally taking shape

Although the old guard took most of the major prizes in 2018, the latter stages of the season provided confirmation that a new order is taking shape, according to Tennishead Editor Paul Newman

The idea that a new wave of players is on the brink of toppling the old guard feels like a scratched record. For how many years have we been predicting that the Federer-Nadal-Williams generation are on their way out and that the dawn of another era has arrived?

On the face of it we are still waiting. Roger Federer, Rafael Nadal and Novak Djokovic once again took the biggest men’s prizes in 2018 and early 2019 – the last time a man under the age of 28 claimed a Grand Slam singles title was Marin Cilic at the 2014 US Open – while Serena Williams made such an impact on her comeback after a 14-month maternity break that she was the favourite to win the 2019 Australian Open. Even when 2018 opened with a woman winning her maiden Grand Slam title it was Caroline Wozniacki doing so at the 43rd attempt.

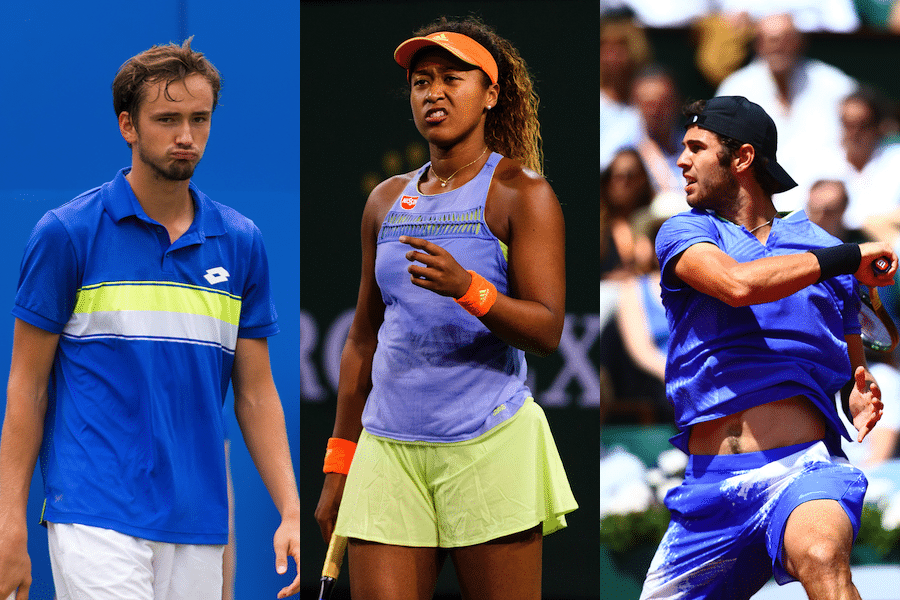

In the closing months of last season, nevertheless, the tectonic plates beneath the tennis landscape might have finally made a definitive shift. To use another metaphor, players who had been knocking at the door finally rammed it open as the likes of Alexander Zverev, Karen Khachanov, Naomi Osaka and Elina Svitolina claimed the biggest prizes of their careers.

Zverev (aged 21) beat Federer and Djokovic in successive matches to win the Nitto ATP Finals in London, Khachanov (22) took the year’s final Masters 1000 tournament in Paris, Stefanos Tsitsipas (20) and Kyle Edmund (23) claimed their first tour titles and Daniil Medvedev (22) recorded his best victory yet by winning the Japan Open.

In the women’s game Osaka (20) won at Flushing Meadows and has since won the Australian Open, Svitolina (24) triumphed at the year-end WTA Finals and Aryna Sabalenka (20) and Daria Kasatkina (21) took two of the biggest post-US Open prizes with their victories in the Wuhan Open and Kremlin Cup respectively.

While it would be foolish to suggest that the ancien régime have had their day – particularly as Andy Murray and Stan Wawrinka will be aiming to put their injury issues behind them and follow in Djokovic’s comeback footsteps in 2019 – there is every reason to believe that they will be pushed harder than ever next year.

That prospect will excite many within the sport, though for tennis promoters and tournament organisers the feeling will be accompanied by trepidation. Although the second highest number of fans (4.57 million) in the history of the Association of Tennis Professionals tour attended this year’s 64 tournaments and the Grand Slam events can hardly build new stadiums fast enough to cope with demand, the interest in the sport has been generated largely by the Federers, Nadals and Williams sisters rather than the Zverevs, Khachanovs and Svitolinas.

Critics of the new wave often suggest that there are no “characters” to fire the public’s interest, but similar sentiments have been expressed ever since Wimbledon spectators lamented the demise of the Doherty brothers more than a century ago. So long as the older players hog the biggest prizes, the tennis public are always going to hear more about them than they are about the younger generation. To appreciate “characters”, you have to be able to see and hear them.

The Nitto ATP Finals in London at the end of 2018 began with a feeling that we had seen it all before as Federer and Djokovic apparently headed for a showdown in the final, but Zverev’s triumph changed all that. What probably pleased the ATP hierarchy most was not the blossoming of the young German’s talent but his engaging speech at the presentation ceremony.

Give these players the biggest stages and we will see whether they have it in them to maintain the sport’s high profile. As far as their tennis is concerned there are plenty of reasons for optimism. Men like Tsitsipas and Denis Shapovalov play with an energy that can light up stadiums around the world. Osaka and Jelena Ostapenko are fearless in their ball-striking. Nick Kyrgios continues to have a McEnroe-like appeal with his brattish brilliance. And Americans will be hoping that Catherine Bellis, Frances Tiafoe and Taylor Fritz can spark a resurgence of the most successful nation in tennis history.

What the sport’s administrators need to do is to provide the environment in which that talent can flourish. Tennis has to recognise that we live in a shifting world where the public’s tastes are changing.

Cricket provides a fine example of that. Around the world Test cricket has been struggling for years – Britain is just about the last country where there is a healthy appetite for five-day matches – but Twenty20, in which matches last just three hours, has reignited interest in the sport. In Australia, for instance, the wonderfully named Big Bash League plays to huge crowds.

It would clearly be wrong to suggest that the Grand Slams – the tennis equivalent of Test matches – are similarly struggling. Indeed, they have become bigger than ever in recent years. However, no sport should rest on its laurels and you sense that if tennis wants to draw in younger fans it needs to appeal to spectators who want more instant gratification. Kevin Anderson’s marathon victory over John Isner in this summer’s Wimbledon semi-finals may have captivated the Centre Court crowd for more than six and a half hours, but how many spectators out on Court 15 sat through the three and three-quarter hours that it took Ruben Bemelmans to beat Steve Johnson in five sets?

Tennis is moving towards shorter matches, albeit slowly. It has its own versions of Twenty20, most notably the FAST4 formula championed by Tennis Australia, and the ATP is to be commended for the experimental short format used at the annual Next Gen Finals in Milan. Match tie-breaks have replaced third sets in doubles matches on the men’s and women’s tours, the Davis Cup now has tie-breaks to decide fifth sets and deciding sets at Wimbledon next summer will go to tie-breaks at 12-12.

Those are all progressive steps, though there are also ways other than shortening matches to engage spectators. For example, allowing on-court coaching in all competitions, as Patrick Mouratoglou, Serena Williams’ coach, argued so well in this article would be a way of helping to reveal players’ characters to television audiences.

Television holds a key to the sport’s future success and one recent survey produced the concerning statistic that the average age of TV audiences for men’s tennis in the United States (61) was lower only than those for golf and horse racing. While the ATP’s decision to sell its broadcast rights in Britain to Amazon Prime (rather than Sky) might not have pleased older generations, the fact is that many younger people prefer to access their entertainment online, on phones and tablets, rather than through a conventional television set.

Tennis also needs to find a way of working together in a more effective way for the benefit of the sport as a whole rather than in the individual interests of the myriad governing bodies. No sides are being taken here in the unseemly to-ing and fro-ing between the International Tennis Federation and the ATP over the future of the Davis Cup, but the fact that no consensus has been reached is to be regretted.

Most people within tennis would agree both that the Davis Cup has been one of the sport’s greatest assets and that change was needed because interest in it was falling and the top players were increasingly avoiding it. If it occupied a sensible place in the crowded calendar – and perhaps if it was played every two years, with a different competition and the Olympics occupying the other slots in a four-year cycle – then the new week-long format bringing 18 different countries together might have a fighting chance of breathing life back into the grand old competition.

However, to stage the climax to the Davis Cup at the end of November and then to expect the leading players to take part in another team event in Australia (the ATP Cup, which will start in 2020) barely six weeks later makes little sense. As it stands, three major team competitions (the Laver Cup, Davis Cup and ATP Cup) will be staged in the space of less than four months from next September onwards.

The case for tennis appointing a global “commissioner” to run the sport has probably never been stronger, thought that stands about as much chance of happening as Wimbledon ripping up its grass courts and changing to clay.

Look ahead to 2019 with our guide to every tournament on the ATP Tour, the WTA Tour and the ITF Tour

If you can’t visit the tournaments you love then do the next best thing and read our guide on how to watch all the ATP Tour matches on television in 2019

To read more amazing articles like this you can explore Tennishead magazine here or you can subscribe for free to our email newsletter here