Survivor: The untold story of Jelena Dokic

The wider world never knew the full story of the horrific physical, mental and emotional abuse to which Jelena Dokic was subjected by her father – until she told the story in her remarkable autobiography

“The blows start getting harder, and then he clenches his hand into a fist and strikes me. The blow to the head fells me and as I lie on the floor he starts kicking me… I pass out… For the next round of torture he makes me stand still, then kicks me in the shin with the sharp-toed dress shoes he is wearing. When I cry out in pain he gets me back in my position, lines up and boots me in the shin again. Again and again he kicks me in my shins…. It hurts like hell.”

That may read like a lurid description of a torture session conducted in wartime, but it is not. It is Jelena Dokic’s account of one of the hundreds of beatings she suffered at the hands of her father, Damir.

This one was carried out in a Toronto hotel room in August 2000, when the future world No.4 was just 17. Her “crime”? She had just lost a gruelling three-set match to a player ranked 13 places above her. The beating went on well into the night and ended only when her father went to get something to eat, having ordered her to sit on the edge of her bed in the dark and not fall asleep or watch television while he was out of the room.

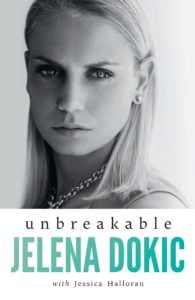

Dokic’s recently published autobiography, “Unbreakable”, is one of the most extraordinary tennis books ever written. The wider tennis world may have been familiar with some of Damir Dokic’s outrageous behaviour – his drunken antics at tournaments, his rows with officials, his accusations of draw-rigging, his threat to “blow up” an Australian diplomat – but what never emerged until his daughter put pen to paper was the full extent of the abuse he inflicted on her. It is a truly shocking story.

Considering the physical, mental and emotional pain she suffered throughout her childhood and teenage years in particular, you cannot help but wonder why Dokic would have wanted to relive it all by writing the book.

“I wanted people to know exactly what went on,” Dokic explains during a break from her TV commentary work at this year’s Australian Open. “As well as my father’s abuse I was a refugee twice in my life. I faced racism and bullying. As a family we were very poor.

“I also battled depression for nearly 10 years and I nearly committed suicide. I wanted people to see my story and understand who I really was. I also knew that my story could help people who could learn a lot from what I went through.”

We talk early in the morning in an almost empty media centre at Melbourne Park, the scene of so many of her most dramatic moments on court. Dokic talks freely about her story, despite the pain of the memories she dredged up in writing the book. “It became quite hard, almost re-living some of those moments,” she admits. “It was traumatic at times.”

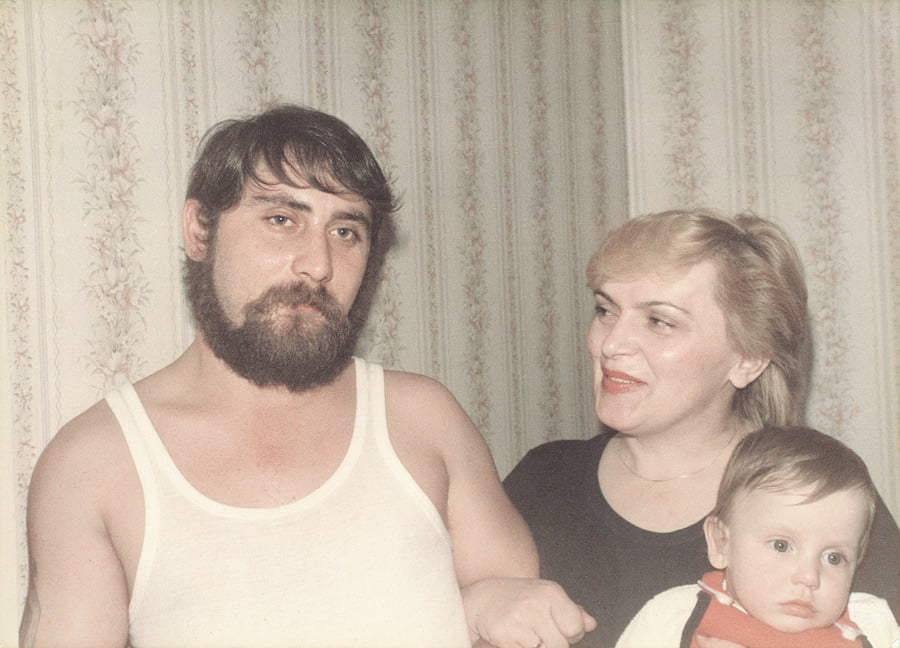

Dokic was born and raised in war-torn Croatia before the family fled as refugees to Serbia when she was eight and to Sydney when she was 11. She had first played tennis at the age of six, when her father decided that he wanted her to follow in the footsteps of another Yugoslav, Monica Seles. From the start he would hit her in the face or send her on long runs if he was unhappy with her practice sessions.

The family’s early years Down Under were very hard, but at a time when they were living on bread and margarine in a cockroach-infested Sydney apartment 11-year-old Dokic won the Australian under-18 title.

It was at this stage that her father started drinking heavily and the abuse became more violent. With her mother and younger brother watching, he would hit her in the face, call her a “stupid cow” or “a whore” and whip her with a thick leather belt. On the day after a beating he would make her wear long-sleeved t-shirts to school or to training to cover up the bruises.

“My father was telling me constantly that I was the way out for the family,” she now recalls. “We very often had nothing to eat. Tennis is one of the highest paid sports in the world and the prize money is only growing. Sometimes that’s the reason why parents push their children.”

The abuse continued throughout Dokic’s teenage years. At 16 she beat Martina Hingis, the world No.1, at Wimbledon, but after losing to Alexandra Stevenson in the quarter-finals her father told her she was “pathetic” and “hopeless”. At their hotel in Putney he made her stand still for three hours while he screamed abuse at her.

Later that summer Dokic lost a match to Conchita Martinez in draining heat in Toronto. Her father refused to let her eat or drink that evening – her last meal had been breakfast – as he beat her with his belt and fists, pulled her hair, spat in her face and verbally abused her until dawn.

After Dokic had lost to Lindsay Davenport in the 2000 Wimbledon semi-finals, her father called her “a hopeless cow” and told her she would not be welcome back at their hotel. At 11pm a cleaner at the All England Club found her on a couch in the players’ lounge. Alan Mills, the tournament referee, arranged for her to sleep at a nearby house rented by her management agency. “At least I didn’t get a beating from [my father],” Dokic writes in her book.

The pain was not just physical. Damir ordered his daughter to sack a succession of coaches she had enjoyed working with, including Wally Masur, Lesley Bowrey and Tony Roche, and regularly made her carry the can for his run-ins with officials. At the 2001 Australian Open he claimed the draw was rigged and announced that Jelena, who had benefited from huge support from Tennis Australia, would represent Yugoslavia in the future.

That remains a particularly painful memory. “Being jeered by the crowd as I went out to play Lindsay Davenport in Rod Laver Arena was one of the worst on-court experiences of my life,” she recalls. “I had really accepted Australia as home. I really loved playing for Australia. I felt Australian. I had a great relationship with the public and with the fans.”

Even after Jelena left the family home at 19 her father would leave abusive voicemail messages and make death threats against her boyfriend. In the hope of placating him she sent him millions of dollars from her earnings and signed over to him a house in Florida which she had effectively paid for. She had a mental breakdown and on more than one occasion was on the verge of throwing herself off the balcony of her 13th floor apartment in Monaco.

Jelena’s career eventually petered out because of shoulder and wrist injuries. She has now cut off all ties with her father, who lives in a luxurious home near Belgrade. “I pretty much ruined myself financially at one stage,” she says, adding that he had benefited from “millions and millions” of her earnings. She says she handed over the money in the forlorn hope that it would ease the relationship between them, particularly after she had left home.

“I don’t know if I would go as far as to say I still love him because you get to a stage where enough is enough,” she says. “I was very loyal to my father and my family. At the end of the day all I ever really wanted was that family unit.

“I don’t hate him, but I certainly hate the things he has done. It’s hard to find any positive emotion towards him. I’m very disappointed, hurt and angry that after I tried to make this relationship work he doesn’t want that. He still thinks to this day he was right. He let our family fall apart and that’s something that’s very hard for me to accept.”

Today Dokic is finding her feet again. She has “a better relationship” with her mother, who lives in Croatia, though she still finds it hard to understand why she did so little to stop the abuse. Jelena is very close to her younger brother, Savo, who lives in Serbia, and says that Tin Bikic, her boyfriend of the last 14 years, has been her “rock”. They divide their time between Melbourne and Zagreb.

Writing the book occupied much of Dokic’s time in 2017 and this year it is being turned into a documentary film, which she is producing. She was busy with her TV commentary work throughout January and is hoping to do similar work at Wimbledon. She has been writing columns, has started motivational speaking and is setting up her own foundation to help victims of abuse.

She has been stunned by the positive reaction to the book. “People are coming up to me and hugging me and saying: ‘You’ve helped me believe and get stronger so that I can leave my own abusive situation’,” she says. “I am so thrilled to hear that.”

What sort of career does Dokic now think she would have had without her father? “I think I would have won a Grand Slam eventually and been world No.1,” she says. “I certainly would have had a much longer career if all of these distractions and everything I went through with my father hadn’t happened.

“I was actually battling depression on tour for about four or five years. When I left home I struggled because my father made me feel really worthless. I had no self-confidence, no self-esteem. On top of all the physical, verbal and emotional abuse, he really broke me down as a person inside.”

Her remarkable book ends with some resounding words. “I don’t want anyone to feel sorry for me – I am luckier than most,” she writes. “I am a survivor. And I will always find a way.”

Read more incredible interviews like this in Tennishead magazine or grab a FREE SUBSCRIPTION to our superb newsletter