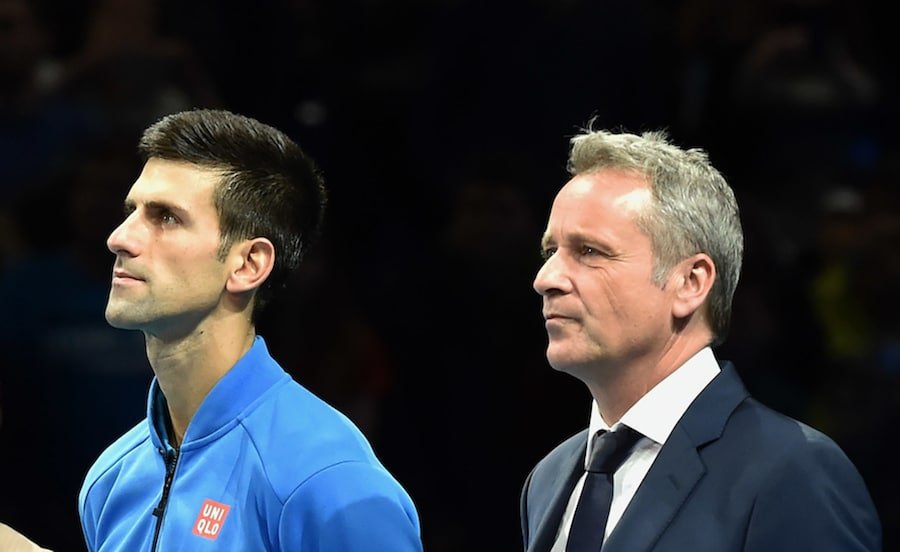

Chaos at the ATP Tour! A major split in tennis’s governing body sees Novak Djokovic playing a key role

The question of Chris Kermode’s future as the president and chief executive of the Association of Tennis Professionals (ATP) has created major splits in the body that runs the men’s tour. Simon Briggs says that Novak Djokovic could hold the key to the ATP’s future direction

Which is the most chaotic administrative body in tennis? This is a crowded field, but the Association of Tennis Professionals – hitherto seen as an island of calm in a turbulent sea – made a late bid for the title this spring.

The two sides of the ATP board – three men represent the players and three represent the tournaments – have rarely been as badly split as they were over the vote in Indian Wells on the future of Chris Kermode, the 54-year-old Englishman who has run the tour as president and chief executive for the last five years. The tournaments all voted in favour of a contract renewal. The player reps all voted against, thus leaving Kermode well short of the “super-majority” (at least two votes of support from each side) that he needed in order to continue.

Why was the decision controversial? For one thing, the involvement of Justin Gimelstob – the commentator and former doubles champion who was recently sentenced for assault – as one of the player reps left an unpleasant taste.

However, the bottom line of politics – sporting or otherwise – is that you can do what you want if you have a broad base of support. And here was the real problem for the anti-Kermode faction. As well as the three player reps, the move was backed by five of the 10 members of the ATP player council, including the council president and world No 1, Novak Djokovic. Outside that room, nevertheless, the decision met with bemusement.

Just before the Australian Open in January, Stan Wawrinka wrote an open letter to Vasek Pospisil, the Canadian who is one of the most vocal proponents of change on the player council. “You emailed us Friday telling us your opinion because of grand-slam money and the players’ voice of the ATP and that we need to change CEO,” Wawrinka said. “I completely disagree and know so many players and so many top players that COMPLETELY disagree with this.”

To those who questioned the wisdom of this boardroom coup, it seemed that widespread apathy within the locker-room had allowed a small number of zealots to dictate policy. Even after the plot to oust Kermode became widely known during the Australian Open, the three player reps and the five-man faction on the player council faced inwards, making little effort to engage with their critics.

In a statement published after the Indian Wells decision, the player reps said that it was “surprising to see the amount of [media] coverage dedicated to this internal governance decision”, then complained about “the suspicions that have been stoked in that coverage” and insisted that “this was not a decision made or driven by one or two individuals’ personal beliefs or agendas”.

In that case, what was it driven by? Nobody would explain why it was necessary to impose a change of leadership against the wishes of both the tournaments and a strong group of high-profile players, including Roger Federer and Rafael Nadal.

At first, Gimelstob seemed the most obvious figurehead and thus the natural person to ask, but his situation was clouded by the charges hanging over his head. In April he was sentenced by a Los Angeles court to 60 days of community labour, three years’ probation and a year of anger-management therapy following an attack in the street on a friend of his ex-wife.

After Gimelstob eventually resigned from the board in late April, the next logical leader for the anti-Kermode group appeared to be Djokovic, but he remained reluctant to comment throughout. In May a reporter from The New York Times, Ben Rothenberg, asked Djokovic about Gimelstob’s potential replacements on the ATP board. “I don’t think it’s fair that you guys point out myself as the decision maker,” Djokovic replied.

So we find ourselves trying to piece together the motivation behind Kermode’s ejection. One starting point might be Pospisil’s letter to players in January, which called for “a CEO that first and foremost represents OUR interests” and added: “Our system is broken and it has been that way since Open era of tennis. The ATP represents the tournaments and we fight and scrape for every inch because we have not acted as a unified body.”

Pospisil is not alone in believing that the players are being exploited by the tournaments and that the problems are structural. Two opposing sides sit around the same boardroom table in a system that cannot help but throw up deadlocks, especially when it comes to the fundamental question of pay deals.

The same argument suggests that the odds are stacked, because the tournaments are represented by experienced businessmen while the player reps tend to be former players themselves with considerably less financial expertise.

Gimelstob was seen as a happy exception to this rule: in Djokovic’s words, “the biggest asset players have had”. In an interview in The New York Times published shortly after he was sentenced, Gimelstob told Cindy Schmerler: “The players know how good I am, especially in terms of improving prize money for them, and that pisses off the tournaments. It annoys them that, even in a compromised state, I’ve been able to outwit, outmanoeuvre, outstrategise and outmobilise them.”

If Gimelstob wanted to reinforce the players’ sense of victimhood, his most powerful argument related to the Grand Slams’ mighty incomes, which, in line with global sporting trends, have continued to rise rapidly while smaller events flatline or worse. According to some calculations, only 12 per cent of the Slams’ revenues are being redistributed to the players, whereas the figures for big American sports leagues such as the National Basketball Association tend to hover around 50 per cent.

The comparison is hardly exact. The NBA does not have to deal with massive facilities sitting empty for 50 weeks of the year, nor is it constructing new stadia, roofs and other facilities on an annual basis. However, the argument still deserves to be addressed and it surely played a part in Djokovic’s appeal to the wider player group at their annual meeting before the 2018 Australian Open, where he asked a legal expert to brief them on the benefits of a players’ union.

While players’ pay has climbed far ahead of inflation throughout Kermode’s six-year tenure (which will come to an end in December unless something dramatic happens), Djokovic and his allies believe that more needs to be done. And if they want to bring about radical step-change, there is really only one lever they can pull: to threaten to withdraw the players’ labour via a strike or breakaway tour.

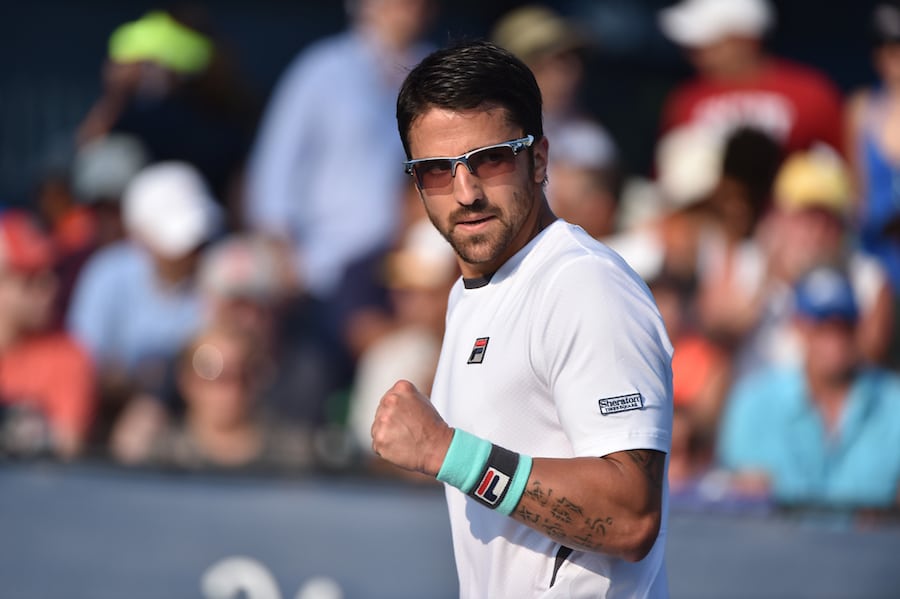

The echoes of such thinking could be heard in an interview given by Janko Tipsarevic – who is not a member of the player council but is a good friend of Djokovic – to the Tennis Podcast in early April. “We need players to realise,” Tipsarevic said, “that there is a possibility to move French Open to Rome, to move Melbourne to Beijing … to believe that Wimbledon can actually be moved to Abu Dhabi.”

When this quote was put to Djokovic in Madrid in early May, he neither endorsed nor rejected it. “They [the Slams] are over 120 years old and we have to respect the history and tradition and everything,” he replied. “But at the same time, we have to balance it with evolution of sport … Whether it’s possible, whether that’s future, we don’t know. I mean, I leave everything open.”

Just how confrontational does Djokovic want to be? This is the great unknown. In the immediate aftermath of the Indian Wells vote, he spoke about trying to “protect the ATP president” – a phrase that probably means the creation of a new chairman’s role on the board to work alongside the CEO. On its own, though, this minor shift seems unlikely to shake up the whole structure in the radical way that the likes of Pospisil and Tipsarevic have been talking about.

The situation remains hard to read. One high-ranking Grand Slam official told me: “A year ago, after all that talk about unions, I thought that Novak’s stance on the ATP was that it didn’t work, and so he wanted to burn the whole thing down and start again. But now, if he wants a chairman on the board, that’s more like trying to change things from the inside, little by little. We’re waiting to see where he goes next.”

So, it seems, is the whole sport.

Simon Briggs is Tennis Correspondent of The Daily Telegraph and The Sunday Telegraph

Look ahead to the rest of 2019 with our guides to every tournament on the ATP Tour and the WTA Tour. If you can’t visit the tournaments you love then do the next best thing and read our guide on how to watch all the ATP Tour matches on television in 2019. To read more amazing articles like this you can explore Tennishead digital magazine here or you can subscribe for free to our email newsletter here