Tennis through the ages: Centre court, centre stage

As the popularity of the sport grew and the appeal of tournament tennis spread, stadiums (now known as a centre court) started to emerge and international stars began to enjoy worldwide fame.

When Maud Watson became Wimbledon’s first Ladies Singles champion in 1884, the world was entering an extraordinary period of technological and social change. Within a few short years, the petrol-fuelled car was invented, the first powered flight took place, and the Paris Metro and the New York Subway opened. Not only could people travel more freely, but they became healthier and lived longer as new vaccines were developed to combat ailments and illnesses that were previously untreatable. In 1884, people’s horizons were local. Just two decades later, world affairs would be on everyone’s minds.

The game of lawn tennis evolved equally quickly. The early players had been well-to-do socialites seeking amusement and exercise. What they could not have anticipated was the rapid growth of tennis as a spectator sport. Even the first Wimbledon final in 1877 had been watched by 200 paying spectators, a clear sign of things to come. Three years later, F.H. Ayres & Company provided two temporary

grandstands for the Centre Court, and by the mid-1880s permanent stands had been erected on three sides of the court, along with a sectioned-off area for the press. The name Centre Court – so synonymous with tennis today – was a logical one, for at Wimbledon’s first home in Worple Road the main court was indeed surrounded on all sides by the other “outside” courts. There are now “Centre Courts” at tournament venues throughout the world, though few are actually centrally positioned.

By the 1890s tennis clubs had been established all over the world, and Walter Wingfield’s garden game was a fully- fledgedinternationalsport. Top-level competition was still for the privileged classes with leisure time to play in tournaments, particularly where international travel was involved. Within countries and continents the train took the strain, but the pioneering few who crossed the Atlantic did so in style in grand luxury liners. The working classes were quite willing to spend a shilling (or its equivalent in cents or centimes) to read illustrated weekly news magazines which focussed mainly on the social activities of high society, and tennis was very much a part of that glamorous lifestyle.

At Athens in 1896, lawn tennis was one of just nine sports included in the first Olympic Games of the modern era, with Ireland’s John Boland earning the distinction of becoming the first Olympic tennis champion. Four years later in Paris, Great Britain’s Charlotte Cooper won the inaugural women’s tennis event to become the first female gold medallist in the history of the Olympic movement.

A new breed of tennis champion emerged in the 1890s to succeed the generation spearheaded in the US by Richard Sears, and in Britain by the Renshaw brothers. The earlier champions had played other racket sports before turning to lawn tennis, and – with one or two exceptions – would never have had the inclination to travel abroad to compete. In the 1890s and early 1900s, however, players like Reggie and Laurie Doherty had styles of play that owed nothing to other sports. They were lawn tennis players through and through, and their achievements testified to their prowess and skill. Reggie won Wimbledon for four straight years from 1897 to 1900, and his brother Laurie then went one better, triumphing in five consecutive years from 1902 to 1906. Incredibly in the 105 years since then, only two Englishmen, Arthur Gore and Fred Perry, have won a Wimbledon singles title.

In 1905, 27 year-old Norman Brookes travelled to England from his home in Melbourne to compete in the Wimbledon Championships. He came very close to lifting the title, winning the All-Comers Singles before losing to reigning champion Laurie Doherty in the Challenge Round. Two years later, he returned and was crowned Wimbledon’s first overseas champion.

Brookes’ victory opened the floodgates of overseas success. New Zealander Anthony Wilding was a sporting idol in the eyes of the public, winning the Wimbledon singles title for four consecutive years from 1910 to 1913 before losing his title to Davis Cup team-mate Brookes in 1914. A year later Wilding was killed in France while serving with the Royal Marines. He was a hero in every sense.

The Davis Cup had been inaugurated in 1900 as a team match between the United States and the British Isles, and had quickly broadened into an international competition involving many nations. Australian Brookes and New Zealander Wilding joined the fray together in 1905 representing Australasia, and that combined team would go on to win the trophy six times before the two nations began entering separately in 1923. The Davis Cup was a powerful driving force in raising standards and developing the sport worldwide, and by 1913 the desire for international co-operation was such that the International Lawn Tennis Federation (ILTF – now known as the ITF) was formed. It had been the brainchild of Duane Williams of Philadelphia, who would sadly never see his grand vision realised, for he was one of the hundreds who died when the Titanic struck an iceberg and sank in 1912. His son Dick swam to safety from the stricken liner, and went on to become a two-times US singles champion. In early June 1914, a precocious French teenager

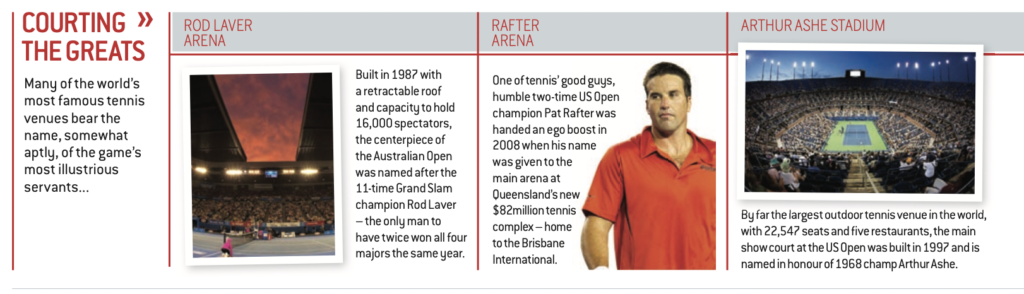

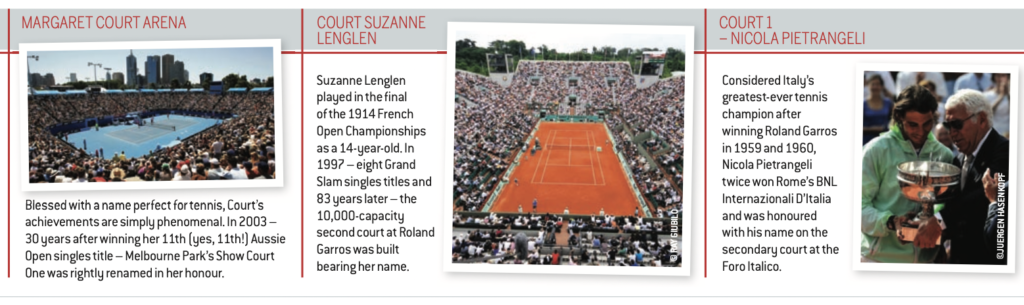

A Davis Cup player and French junior champion in 1945, Philippe Chatrier went on to serve as president of the International Tennis Federation between 1977 and 1991. A year after his death in 2000, the Centre Court at Roland Garros was re- named in his honour. won her first major title, the World Hard Court Championship at St. Cloud. Suzanne Rachel Flore Lenglen had been born in Paris in 1899, and her talent, personality and unparalleled success would one day bring a huge global audience to lawn tennis. However, her arrival on the world stage was to be delayed for five long years.

During the 1914 Wimbledon Champion- ships, Archduke Franz-Ferdinand, heir to the throne of Austria-Hungary, was assassinated in Sarajevo. This triggered a chain of events that would quickly lead to the outbreak of World War 1. For the next four years, the progress of lawn tennis was halted.

This feature was orignally published in Tennishead magazine back in 2007 and you can grab your own annual subscription, which includes 4 stunning printed magazine editions and 24 issues of The Bagel newsletter.

![]() Join >> Receive $700/£600 of tennis gear from the Tennishead CLUB

Join >> Receive $700/£600 of tennis gear from the Tennishead CLUB

![]() Social >> Facebook, Twitter & YouTube

Social >> Facebook, Twitter & YouTube

![]() Read >> World’s best tennis magazine

Read >> World’s best tennis magazine

![]() Shop >> Lowest price tennis gear from our trusted partner

Shop >> Lowest price tennis gear from our trusted partner