The story of Wimbledon, exclusively told by the BBC’s ‘voice of tennis’

Nobody is better placed to tell the story of Wimbledon, from its 19th century origins to the present day, than John Barrett, who has missed only one day at The Championships in the last 70 years. The BBC’s former voice of tennis, whose official history of the All England Club has just been updated and republished, talks to Paul Newman

Queen Mary present Suzanne Lenglen with one of 34 commemorative medals that were given to surviving champions in 1926

The coronavirus pandemic has changed almost everyone’s routines, but imagine what it must have been like for a man who had spent the same 13 days at the same event every year since 1950, only to be denied the chance to do so again this summer. “It was very strange,” John Barrett admits as he looks back on his Wimbledon-free July. “I live at the Championships for the entire fortnight every year. This summer was all very unreal.”

Barrett, the BBC’s former voice of tennis, is probably the only person who has attended every Wimbledon since his first visit in 1947. Indeed since 1950 he has missed only one day at The Championships, when he attended his son’s graduation ceremony. This year, however, for the first time since the Second World War, the most famous venue in world tennis fell silent, victim to the pandemic that has raged across the planet.

“We did what everybody else did – we stayed at home,” Barrett said as he recalled how he and his wife Angela, Wimbledon singles champion in 1961, had spent the fortnight. “We watched a bit of the tennis on the BBC and we phoned the friends we might have been expecting to meet at the Championships.”

One compensation for Barrett, nevertheless, might have been the opportunity to browse through the fifth edition of his magnus opus, “Wimbledon: The Official History”, which was published this summer. The original book took nearly three years to write and Barrett describes it as a labour of love. It is a remarkable publication, full of fascinating stories and wonderful photographs, from the establishment of The Championships 143 years ago through to the modern day. Barrett painstakingly records how The Championships built on a modest start – there were just 22 competitors in the first tournament in 1877 – to become the game’s most prestigious tournament and tells the stories of the men and women who have coloured its rich history.

“He was a very good player who played with two hands on both sides”

There could be no better man to recount those tales than 89-year-old Barrett, who started covering tennis for the Financial Times in 1963 while he was still playing, edited the “World of Tennis” annual for 23 years and became one of the sport’s most respected historians. He commentated for the BBC from 1971 until his retirement in 2006.

Lew Hoad (left) and Ken Rosewall, who both beat John Barrett at The Championships, contested the Wimbledon final in 1956

Barrett had already made his mark on schools tennis when his first visit to The Championships, as a spectator in 1947, instilled a burning ambition to return as a player. The first match he saw was a straight-sets victory for the American Bob Falkenburg over the Belgian Philippe Washer. “I remember thinking: ‘Washer must have the fastest serve in the world’,” Barrett recalled. “Of course he didn’t, but to my untutored eye he served like a monster, crashing down his serves.”

Within three years Barrett was making his debut at The Championships, losing in the first round of the doubles (alongside John Horn) to Budge Patty and Tony Trabert, both future singles champions. Twelve months later Barrett played his first Wimbledon singles, but won only three games against Canada’s Lorne Main. “He was a very good player who played with two hands on both sides, which puzzled me,” Barrett recalled. “I didn’t know how to deal with it and I completely froze. I was very nervous.”

Barrett played at The Championships every year between 1950 and 1970, except for 1963 and 1964. Two years after completing his national service, he had started working for Slazenger. “In 1963 the LTA brought in a daft rule, that if you worked for a sporting goods company you couldn’t play in any of the tournaments where their ball was used, so for two years, until they dropped the rule, I wasn’t allowed to play,” he said.

“It was the sort of silly rule that the amateur game was cursed with. You also weren’t allowed to travel abroad to play tournament tennis without the permission of the LTA. We saw ourselves as serfs of our national associations. That was why it was very important that the ATP was founded in 1972 as a players’ union – a true association of tennis professionals. Since 1980, of course, it’s been a partnership with the tournament directors.”

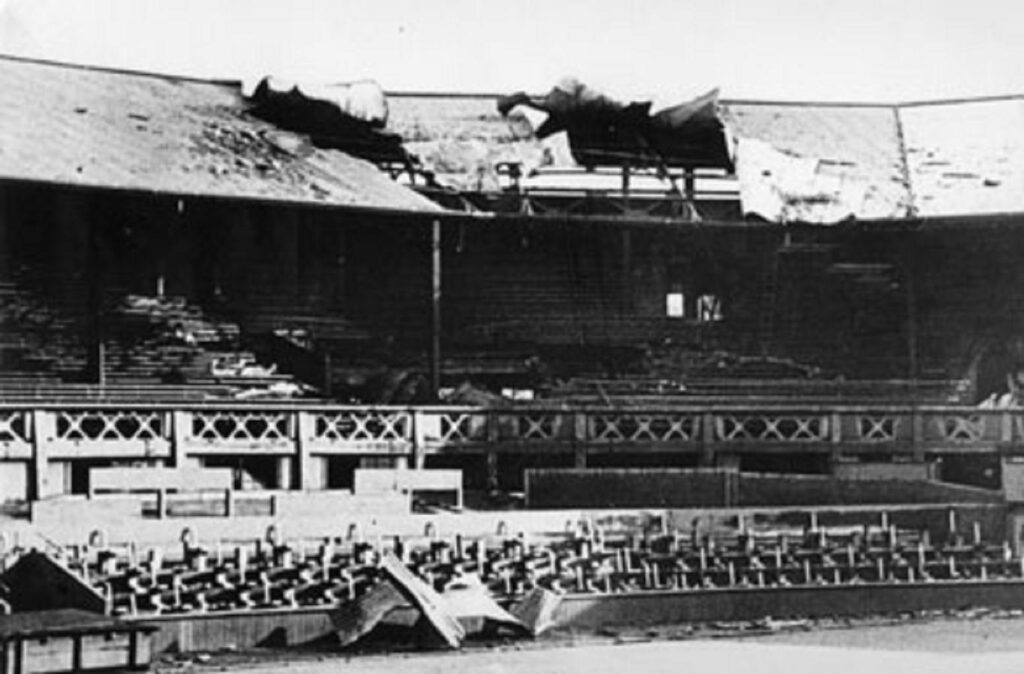

A German bomb landed on Centre Court in 1940

Barrett, a left-hander, reached the third round of singles at The Championships four times and lost to some of the sport’s biggest names, including Ken Rosewall, Lew Hoad, Roy Emerson and Mal Anderson. Barrett also lost his only meeting with Rod Laver, in the second round of the British Hard Court Championships at Bournemouth in 1968, which was the very first tournament of the open era.

A former Davis Cup captain, Barrett believes that having played the game informed his later work in the commentary box. “You shouldn’t have commentators who have never played,” he said. “You have to understand what the players are feeling and you only know that if you’ve played at a reasonable level. I was a good player – not a great player, but I had won tournaments and I knew what it felt like. I was very friendly with all the top Australians of my day and I got a lot of help from them with their insights.”

Barrett refuses to be drawn into any “greatest of all time” debates, saying it is impossible to compare different eras. Asked to name the greatest matches he has commentated on, he chooses two, neither of which were at Wimbledon: Rafael Nadal’s five-set, five-hour victory in the 2006 Rome final over Roger Federer, who missed two match points with netted forehands, and Rosewall’s four-set victory over Laver in the World Championship Tennis Finals in Dallas in 1971.

“The Club has taken great care to keep the same atmosphere of tennis in an English garden”

“I had been warming Ken up in the lead-up to the final because he wanted to hit with a left-hander,” Barrett recalled. “We had noticed that in the corner of a service box at one end there was an uneven patch of court. I said to Ken: ‘Look, here’s a place where you could aim your serves.’ He hit it about four times in the match and won the point each time. Laver got quite annoyed about it.

Martina Navratilova congratulates Steffi Grafafter the German’s victory in the 1988 final, which John Barrett considers one of the greatest Wimbledon matches he has seen

“The winner’s cheque was for $100,000. When I went back to the locker room I found that Ken had left it on a bench by mistake. I took it and hid it in my pocket. I said to him later: ‘Can I look at that cheque?’ Ken started searching for it but then said: ‘Oh no, what have I done? I’ve lost it.’ I teased him for a bit before I gave it back to him.”

Asked to name the greatest Wimbledon matches he has seen, Barrett picks out Federer’s victory over Andy Roddick in the 2009 final, when the American dropped his serve for the only time in the final game, Novak Djokovic’s triumph over Federer in last year’s marathon final and Steffi Graf’s victory over Martina Navratilova in the 1988 final.

“That day she did so and came back from a set and a break down to beat Navratilova. It was a terrific match.”

“Steffi had always had a very good sliced backhand,” Barrett recalled. “In practice, playing against her coach, Pavel Slozil, she also used to hit over the ball on her backhand, hitting some cracking drives, but she never struck those shots in matches. That day she did so and came back from a set and a break down to beat Navratilova. It was a terrific match.”

In 2016 Andy Murray won the men’s singles for a second time, 139 years after Spencer Gore emerged as Wimbledon’s first champion from a field of just 22 players

Andy Murray’s two Wimbledon triumphs are also treasured memories for Barrett, who for years had thought he would never see another British man follow in the footsteps of his great friend, Fred Perry. “Andy has been marvellous for British tennis, for world tennis, a breath of fresh air,” he said.

Barrett admires the way the All England Club has updated and innovated without damaging its essential character. “The Club has taken great care to keep the same atmosphere of tennis in an English garden,” he said. “Somebody who hasn’t been there for 50 years wouldn’t recognise the place at first, but they would still feel the same about it, because it retains the same feel. I think the care not to allow advertising on the show courts to take over the scene has been particularly important, especially when you look around the rest of the world.”

While some traditionalists did not approve of the slowing down of Wimbledon’s courts 20 years ago, Barrett thinks it helped to make the game more attractive. “You can now have long rallies, which you didn’t in the old days,” he said. “When matches from the Sampras and Becker eras were dominated by serve-and-volley it could be a little tedious because the points were over quickly. You didn’t have the same excitement of rallies that Federer and Djokovic can give us.”

Barrett hopes that Wimbledon never allows on-court coaching (which he calls “disgraceful”) and would like to see a stop to players receiving physical treatment on court. “You’re either fit to play or you’re not,” he said. “If you want to have treatment, treat yourself: get out a bandage and strap your own ankle.”

However, he likes the idea of shot clocks to limit the time players take between points. “There’s no question that some players push the thing to the limit,” he said. “They bounce the ball 20 times. Frankly it’s a form of gamesmanship.”

As for those people who have followed him into the commentary boxes, Barrett respects John McEnroe’s opinions – though he thinks the American “talks too much and sometimes at the wrong time” – and rates Andrew Castle highly. “Andrew doesn’t over-talk,” Barrett said. “So many commentators talk over the points, which is so irritating. We always used to have this dictum from the BBC and it’s one I’ve always believed in: never get between the viewer and the action.”

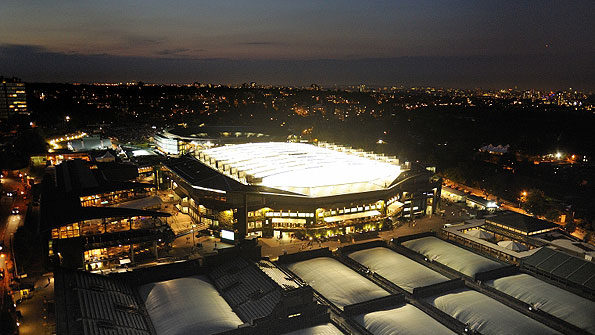

2009 was the year that the new retractable roof was used on Centre Court for the first time

- Join the tennishead CLUB and receive £250/$350 of FREE GEAR including ASICS Gel-Resolution 8 trainers, shorts, shirt & socks

- Keep up to date with the breaking news & tennis action at our tennis news section

- Win amazing prizes by entering our competitions

- Learn more about your favourite players including Roger Federer, Rafa Nadal and Novak Djokovic

- Check out the latest tennis equipment with our tennis gear reviews

- Receive regular updates in our legendary free newsletter

- Read in depth features with stunning photography in tennishead magazine

- Can’t visit the tournaments you love? Check out our guide on how to watch tennis on TV

- Don’t miss a thing with our Live Scores service

- Follow tennishead on social media at Facebook, Twitter, Instagram & YouTube

- EXCLUSIVE 5% DISCOUNT for all tennishead readers on tennis rackets, balls, clothing, shoes & accessories with All Things Tennis, our dedicated tennis gear partner